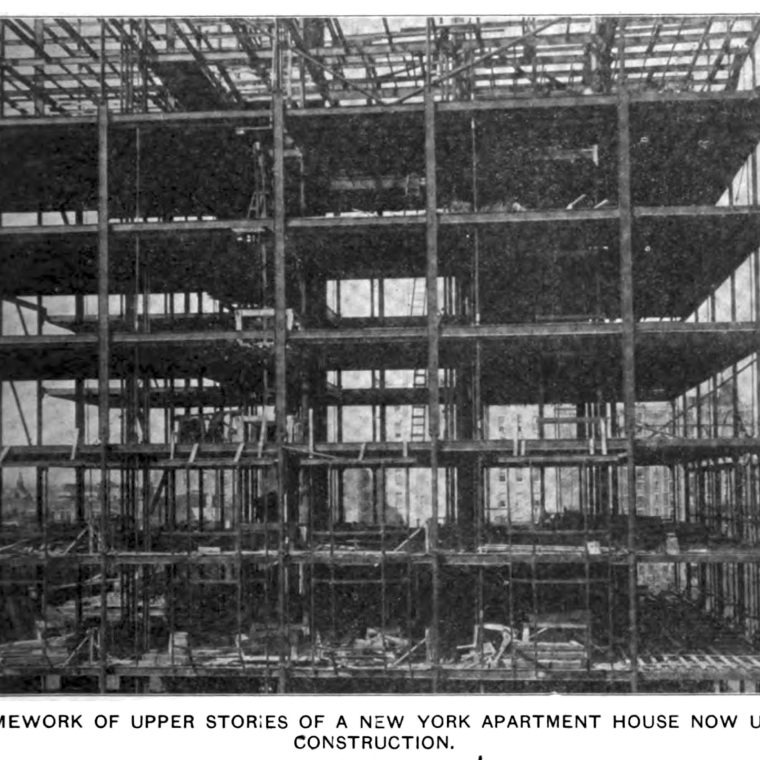

If you look closely at that picture, something funny is going on at the third floor level up from the bottom. The columns are significantly bigger above that floor than they are below, which does not happen often in modern steel framing and happened even less often with cast-iron columns. What’s going on here?

The picture is from an April 14, 1904 article in the Engineering News titled “Current Practice in Apartment-House Construction in New York City.” That date is not random – a few weeks earlier, an apartment house called the Hotel Darlington had collapsed catastrophically during construction, killing about two dozen people. The article was both a reaction to that disaster and restating a concern that had been expressed multiple times in the professional engineering press: too many large buildings were being built without proper engineering design.

The building in the picture was to be 11 stories high and the frame was “nearly completed” with “three of four stories” out of the picture frame at the bottom. The peculiarity I mentioned is explained, but the explanation doesn’t make me any happier than it made the article’s author: “The columns of the lower half are of cast-iron, while those of the upper half are of steel. The change is made for the reason that steel sections make the cheaper column after the limiting minimum size of cast-iron column fixed by the Building Law is reached. In this building the change of the structure was made at about the middle of the height.” That second sentence is worthy of some explanation.

Any time multiple variant systems are in use in construction, it’s a fair bet that their costs, under some analysis, are similar. If one system were much more expensive, it would fall out of use. Under the 1901 New York City Building Code, this building had to be “of fireproof construction” or it would have been limited to 7 stories and 85 feet in height. Using fireproof construction, it could be up to 12 stories and 150 feet high if it fronted on a street 75 feet or more wide and up to 10 stories and 120 feet high if it fronted on a street less than 75 feet wide. (Typical Manhattan side streets are 50 feet wide, while avenues are 75 or 100 feet wide. So this building faced an avenue or one of the major, wider crosstown streets.) The minimum column size in the quote was fixed at 5 inches diameter with the iron shell 3/4 of an inch thick. So if a steel column could be fabricated for a lower cost than that minimum iron column, it was cheaper to use, as described.

This logic only makes sense if you’re looking at columns solely for their concentric gravity load: the tabulated maximum load that they could carry if loaded purely in compression. Since cast iron is far stronger in compression than the steel available in 1904, the iron columns will be smaller. This simplistic analysis works okay if you’re building a bearing-wall building and only have columns at the interior. But in buildings where the structural function has been removed from the masonry, like the building shown “of iron frame and curtain-wall construction”, the columns will definitely be subjected to combined bending and compression. The tables will be wrong.

The switch in metal-frame building technology in the 1890s is often presented as a material change: steel columns replaced cast-iron ones. But a much bigger conceptual change also occurred: frames replaced individual columns and beams as the structural model of the building. This happened faster in commercial-building design than in apartment design, which is why the News article has the title it has.