The Library of Congress simply describes this photo as “Bridge over the Susquehanna, Pittston, Pa.” There are a lot of bridges over the Susquehanna River: it’s one of four large rivers in the northeastern US that run more or less north-south (the Susquehanna feeds into Chesapeake Bay, the Delaware feeds into Delaware Bay, the Hudson feeds into New York Bay, and the Connecticut feeds into the Long Island Sound) and therefore was seen as an obstacle during the era of railroad construction.

Pittston is a small town about halfway between Wilkes-Barre and Scranton, which puts it firmly in the Pennsylvania “Coal Region.” Railroads in this area carried all the usual traffic, including of course passengers to the towns and cities there, but their main business was carrying coal to the big cities nearby – Pittsburgh to the west, Philadelphia to the southeast, and New York slightly south of east. The Delaware, Lackawanna & Western Railroad took the central route from the coal region to New York harbor; the Erie Railroad took the northern route; the Central Railroad of New Jersey took the southern route. Except for the short commuter lines that feed into NYC, these railroads did not survive the mid-1900s, because they served areas without enough population to provide an economic reason to continue once coal shipments started to decline.

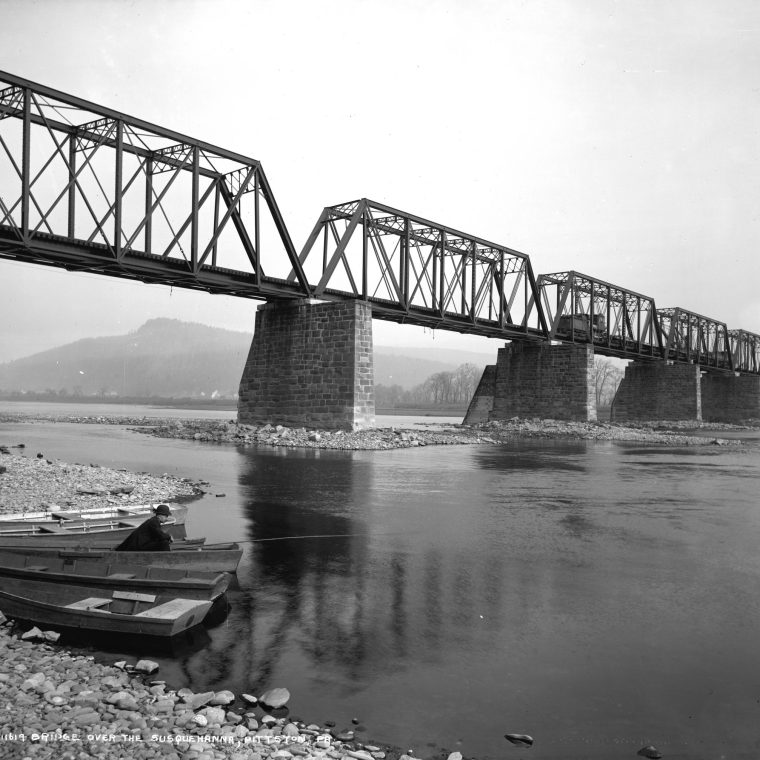

The bridge was built by the DW&L – usually referred to as the Lackawanna, as that name prevents confusion with any other railroad – probably in the 1890s. As can be seen, the river is wide and relatively shallow; it generally does not flood very high. The engineers of the Lackawanna were quite creative when they needed to be, but obviously felt no need to stretch here. The bridge has seven relatively short spans, each a through Pratt truss. The bridge was heavily braced against wind load, with (a) each pair of verticals connected by a lattice girder at the top to form a portal frame, and (b) the usual top-plane cross-bracing. The number of river piers could have been reduced by using much bigger and heavier trusses, like some of the other bridges I’ve shown, but that would have made the superstructure more expensive without necessarily making the foundations much cheaper. In short, this design got the job done and that’s all the railroad needed or wanted.

When I start one of these posts with an old photo, I don’t know where they will end. In this case, the bridge was abandoned long ago. It was purchased by a demolition company (for $500!) in 2007, as part of a plan to sell the steel for scrap, but nothing happened. Parts of the masonry piers were damaged by a flood in 2011, leaving it in poor condition. Apparently some repairs were made by the state of Pennsylvania, but it was demolished in 2017. If the bridge served no purpose, any money spent to repair it would have been money taken from some other project, but it’s hard to believe that no use could be found for it.

A few thoughts about preservation come to mind, all of which I’ve said before but can be repeated in the context of this bridge and particularly the reporting on its demolition. First, the way to preserve a structure is to keep it in use. A bridge or a building that is used has a constituency and a budget. Second, the cost of maintenance is less than any other option. Had the damage to the piers been addressed in 2011, it would have been cheaper than the demolition and the bridge would still be there. Finally, the issue that some people thought the bridge was a landmark and some thought it was an eyesore: objects in the built environment don’t matter to us because they are landmarks. We make them landmarks because they matter to us. The bridge was an inanimate object without feelings, but it mattered to some people.