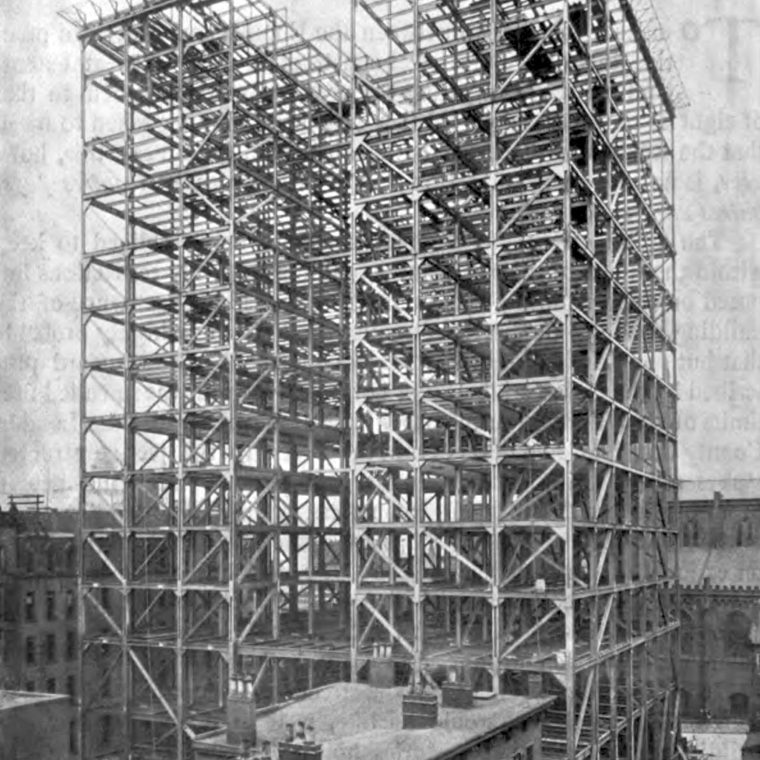

By now, I’ve shown so many pictures like the one above that I feel like anyone reading can probably pick out the main points. That’s the frame of the Carnegie Building in Pittsburgh, as published in “American and English Practice in Architectural Steel Construction” in the Engineering Magazine, May 1898. The author, Charles Childs, makes an interesting claim to expertise for the title comparison: he was the steel designer for the Carnegie Building and for the Hotel Russell in London, seen here:

I’d argue that the choice of those two photos comes close to propaganda: the American steel frame unencumbered by masonry or, for that matter, anything that would make it a useable building rather than a vast jungle-gym; the English columns swallowed up in a heavy brick wall. Childs was more honest that that, and also included the following picture of the Bovril Building in London, looking much like Carnegie:

The text is interesting. Childs says that in an American steel-frame building “each story is supported entirely by girders at the floor-level of that story”, which is a pretty good definition of skeleton framing. He contrasts that to the UK practice of “plac[ing] all necessary bressummers at the level of the first floor” or in other words supporting the masonry walls only at the bottom of the building rather than at each floor framing level. The use of the word “bressummer,” which in American practice has only ever been used with wood framing, is interesting in itself: steel framing in the US evolved in part from truss-bridge engineering, while that word suggests that in the UK it may have been more the replacement of timber elements with steel.

(This is a good place to add that I am far less familiar with the history of steel framing for buildings in the UK than I am with the history in the US. I’m taking what Childs has to say about UK practice at face value and trying to understand it because I don’t have the perspective to say if he was wrong. What he had to say about US practice is correct.)

In that context, the second picture, of the Hotel Russell, shows the girders at the ground level that will support masonry walls above. Childs quotes the London building laws as requiring space left for movement at the end of every bressummer, equal to 1/4 inch per ten feet of beam length, and thus forcing into practice the use of slotted holes where these big girders meet exterior-wall columns. In US practice, girder-to-column connections were always riveted and assumed to have no capacity for lateral movement of the beams relative to the columns. Assuming he is correct about his understanding of the London law – and other sources I’ve read indicate similar requirements in London at the time – it shows a fundamental difference in approach. Steel-frame buildings in the US relied solely on the frame for structural capacity, and everything else was worked around that. Leaving expansion room at the ends of girders supporting masonry walls above makes perfect sense if you view your buildings’ vertical structure as primarily masonry and you are concerned about thermal movement in a fire causing the walls to collapse.

Childs points out that leaving that expansion room greatly diminishes the wind bracing capacity of the steel, which didn’t matter for the relatively short and stocky buildings being constructed in London but would have been dangerous for American skyscrapers. Both approaches are legitimate based on their assumptions, but the assumptions are quite different. Over time, as tall buildings were constructed in more and more places, the “American” system of providing a steel frame that worked on its own became the more popular approach.

So: propaganda or legitimate emphasizing of differences? Pick a side.

You must be logged in to post a comment.