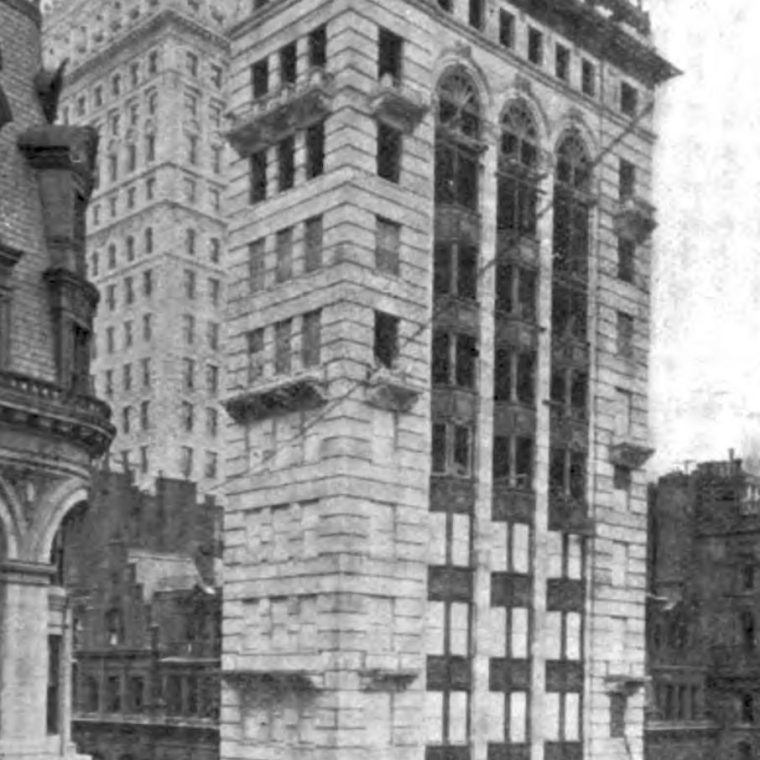

I was recently researching the 1897 Gillender Building, for a group research project that I’ll be talking about at some point in the future. The building was demolished before it was twenty-five years old, but for far longer than that held a record as the most slender skyscraper built. As freaks go, Gillender was quite attractive. It was demolished before its time because it was simply not a money-making endeavor, and money is the reason behind nearly all skyscrapers.

Because the building was so slender – 26 feet wide and 273 feet high – its design was largely controlled by wind resistance. For example, the foundation loads were too high for the wet sand sub-grade, despite the small amount of floor area per column, so caissons down to rock were used. The caissons supported masonry and unreinforced-concrete piers, which supported steel grillages set in concrete, which supported the columns.

The building frame was one bay wide and five bays long. It was a moment frame using built-up girders and columns, which was a common type in the 1890s. So far, a reasonably interesting old building that was among the tallest but not very famous because it site is known for its much more famous replacement.

If you look on the End Elevation at the 10th floor, you’ll see the phrase “Wind Girder.” When I started engineering work in 1987, lateral-load system girders were still often called that in NYC, because we hadn’t yet adopted seismic design as a requirement.

Looking at the Engineering Record article that these illustrations came from, it occurred to me there’s another language lesson to be had. The caissons used in most NYC building foundations are open caissons, where the caisson top is open to the air. The caissons used at Gillender were pneumatic caissons, which are enclosed boxes full of air pressurized to keep water out that are lowered into the ground as the workers inside them remove soil below them. If you look at the second illustration above, Section Z-Z of Figure 1, you’ll see that the water table is at the top of the piers (or, if you prefer, the bottom of the grillages). That’s a fair amount of water pressure at the final, lowest elevation of the caissons. Similarly, the wind girders in the short direction of the frame and at the end bays of the long direction are lattice girders that are really small trusses.

The issue with these names is related to a problem that every non-engineer editor has had with engineer authors: we use words funny*. There is little room in engineering design for ambiguity, so anglophone engineers** pick a meaning for a word and don’t let it vary. “Caisson” has at least three major meanings: (1) a large ammunition box or a wagon outfitted as a large ammunition box***, (2) an open caisson, and (3) a pneumatic caisson. The adjectives in the last two definitions are critical for an engineer to understand what another engineer meant in description.

The word “girder” does not actually describe a material object. It describes a function. A girder-beam, usually abbreviated as “girder,” is a beam that carries other beams. A wind girder is a beam that is part of the wind-load resisting system. A truss girder is a small truss**** used to carry beams or to act as a wind girder…and it’s what we have at Gillender. If you look at the framing elevations, you’ll see plate girders – girder beams built up of plates and angles – and wall girders, which are truss girders.

The habit that many engineers have in writing is to concatenate all of the adjectives necessary to completely describe a structural element, which leads to precise but unwieldy sentences. If I were to write “the horizontal elements in the short-direction bays of the lateral-load system are steel parallel-chord warren-truss lattice girders” it is crystal clear from an engineering perspective but an abomination of language.

* Not “ha ha” funny. More like “editors pulling their hair out” funny.

** I don’t know if this problem exists in other languages. English – a combination of old German and old French, with poorly defined and contradictory rules – is particularly subject to this kind of problem.

*** Over hill, over dale,

We will march the dusty trail,

And the caissons go rolling along.

**** Usually a parallel-chord Warren truss in design.

You must be logged in to post a comment.