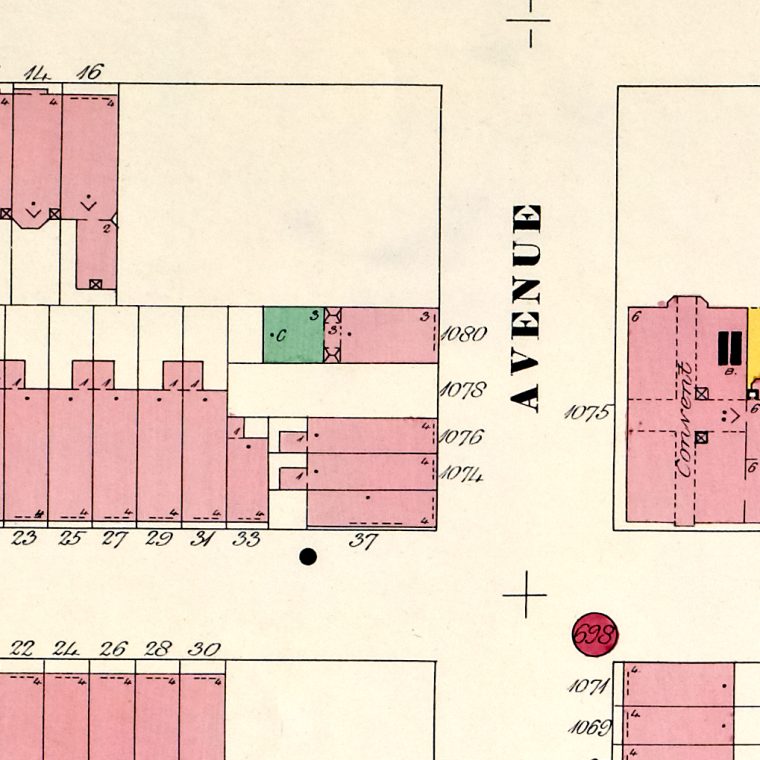

The 1896 Sanborn Map, above, shows a vacant lot at 1078 Madison Avenue. A while ago I became interested in why that lot was vacant at that time, and the answers show a bit about the usefulness and limitations of historical research in our field.

The basic facts are simple: a five-story, one-lot apartment house – something nicer than a tenement but less than the grand apartment houses under construction on the West Side and in midtown at that time – collapsed during construction on September 26, 1896, killing one worker and badly injuring nine others. It was a bearing-wall building with brick walls and wood-joist floors, so this was not a failure of new and unproven technology. Beyond those facts is a distressing truth: I’ll never know for sure what happened. The best I can do is read through various summaries and try to work out what I think is the most believable.

- The New York Times article on September 27, 1896, describes the damage as the rear wall collapsing, which precipitated collapses in the side walls. The rear wall was up to the third-floor level at the time.

- The Brooklyn Eagle article on September 27, 1896, gives much more detail and human-interest color to the story (reflecting the differences between the Eagle and the Times) but also states that all of the walls were up to the third floor at the time of the collapse, that the fire-fighters who responded to the collapse tore down what was left of the walls, and that the architect, Thomas Graham, said that the collapse was caused by “unsound foundation walls.”

- The New York Journal article on September 27, 1896, is similar. It says that “the front half of the building remains standing.” It makes a point of saying that the side walls were not being tied to the neighboring buildings “with the iron ties used by careful builders.” This mistake – it has never been common or good practice to tie your building during construction to its already-built neighbors – suggests that the reporter was not familiar with construction. Graham’s theory about the foundation was repeated. And “The whole construction of the building, as may be seen from the remains of it, is flimsy in the extreme. The girders, 2×12, are lighter than are usually used in a five-story building.” Again, there’s a basic lack of construction knowledge on display: joists are not girders, and the height of the building has little to do with the required strength of the floor joists.

- The New York Times article on September 28, 1896, described the Building Department as conducting an inquiry headed by “Mr. Rutherford”, the assistant superintendent. It is not surprising that a fatal collapse would get the second-highest official in the department involved. The article specifically states that there was no comment by Stevenson Constable, the Superintendent of Buildings. Before the department had completed its investigation, the police arrested Patrick Roche, one of the owners of the construction firm that had been working on site. A coroner’s inquest was set for October 1896. The second half of the article was dominated by Rutherford giving an informal report on his findings: “This is one of the worst pieces of work I have ever seen.” The foundations should have been at least 30 feet deep because the site is “filled ground” but were about six feet deep. The mortar does not stick to the brick, and bricks can be pulled from the wall by hand – “There is no binding quality to the cement or mortar.” The ends of the wood beams were not fire-cut. Some of the walls were on wood foundations rather than masonry. The report asked whether the kind of quality control that Rutherford said was missing was the responsibility of the department, and got the response that “To prevent work of this sort it would be necessary to keep an Inspector here all the time, and in the crippled condition of the Building Department this is impossible.”

- The Engineering News, on October 1, 1896, unsurprisingly provided more technical details, saying that the foundations had settled and cracked before the accident, the walls were not the proper thickness, the mortar did not adhere to the brick, the brick was badly laid up, and the chimney flues were only lined with terra cotta at the locations accessible for inspection. That last item was part of the News editorializing along the lines of Rutherford’s interview: the Building Department had in 1896 a budget of $265,000 to oversee $90,000,000 of construction and a staff of 57 inspectors for 4200 projects. The conclusion is in the lead sentence of the short article: “The collapse of a flat building under construction at 1078 Madison Ave., New York City, on Sept. 26, has revealed a terrible reckless character of construction and disregard of the building laws, while it also appears that the Building Department has not a sufficient force of inspectors to properly supervise the building work in progress.”

- The Engineering News, on October 29, 1896, reported the results of the coroner’s inquest: the responsibility was divided between the construction company’s superintendent, the mason who built the foundation, and the Building Department. The jury stated, in part, “We hold responsible the Department of Buildings of the city of New York for insufficient inspection. We deplore that a lack of finances tie the hands of the Department of Buildings, while the laws calls upon it to perform inspections, which, under the present conditions, are practically a physical impossibility to the available force.”

- The Engineering Record, on October 31, 1896, also reported the results of the coroner’s inquest. The article quoted the same sentence from the jury but provided more detail on the findings: bad mortar, bad stone, bad workmanship, and the “lumping system” of doing work (a fixed lump sum).

- As a coda, the Proceedings of the Board of Estimate and Apportionment of the City of New York reported on December 28, 1896, that William Olcott, the District Attorney, had requested that a $2500 fund be set up to to pay for Department of Buildings investigations “now being made…in conjunction with and under the approval of my office.” The investigations were presumably for prosecutions of the two men named in the inquest, and the department’s “technical knowledge” was needed. The request was approved unanimously.

So what do we know? Most likely the masonry work was of such poor quality that the building was not stable at three stories height…which is remarkably bad masonry. We know that the Building Department and the engineering press felt there was strong evidence of wrong-doing on the part of the builders and the coroner’s jury agreed. We know that the Building Department and the engineering press wanted a larger budget for inspectors, and the coroner’s jury agreed, possible more strongly than the department wanted. We don’t know what Thomas Graham’s involvement was. Did he see bad foundation work? Did he attempt to address the poor quality of the work? Was his statement to the press an attempt to deflect blame away from himself? We don’t know why Stevenson Constable, a man who was quoted in the press time and again on other disasters, kept so quiet about this one.

What’s missing here is some kind of first-hand account from the Department of Buildings, but I suspect that may no longer exist. The department, pre-digitization, had a policy of getting rid of the files for buildings when they were demolished. I suspect – I don’t know – that a similar policy was applied to whatever records of inspections were kept apart from the individual building files.

What I’ve described here is the problem of epistemology in the field of history as applied to buildings. The difference is that historians are generally comfortable with the idea that we construct narratives of the past without knowing exactly what happened, while engineers prefer more certainty.